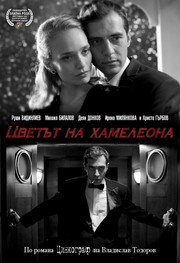

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Color Of The Chameleon (2012) Film Review

Long-time cinematographer Emil Christov's debut feature is an audacious affair, mixing a spy thriller storyline with pastiche, Eastern European secret police satire and a good dollop of absurdist humour. If Eugene Ionesco had written Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, it might have looked something like this.

In fact, it is scripted by Vladislav Todorov, adapting from his own novel Zincograph, and will best reward those who are prepared to pay attention and stick with its twirls and pirouettes until the complex pay-off.

Ruscen Vidinliev plays Batko, an orphan brought up by his aunt with a penchant for onanism, a love of logic puzzles and an ability to lie with ease. What is true about him and what fiction are difficult to pin down - even the story of his own early childhood, recounted to him by his aunt, is suspect. Set initially the communist era, he is recruited by the secret police for his "twisted imagination and supressed fear", chooses the codename "Marzipan" and is told to infiltrate an underground group called the Club for New Thinking, who are studying a book called Zincograph. In one of the many absurdist touches, he soon finds out that the reason for the infiltration is not because of the contents of the book - which is freely available - but because the group have the cheek to meet in secret. In another moment of deadpan humour, he is given a blue egg and a red egg and told to break open one or the other in the event that communism falls in either Russia or Bulgaria. The Matrix was never as complex as this.

The novel, incidentally, is about a "resistance fighter and a zinc plate engraver" - which in the film's continual marrying of fact to fiction is the job Batko is told to take as a cover. But when he falls foul of the rules thanks to one of a series of unfortunate events with his buxom landlady, he finds himself out of the spy game. Undeterred, he sets up his own department - acronymed SEX - and sets about recruiting members of the Club for some kinky missions, with the reasons only becoming fully apparent late in the runtime. Somehow, Christov and Todorov also find time to include a romance subplot, centred on Bulgarian bit part actors in Casablanca, who longed to escape to America, which mirrors - an object featuring at key points in the movie - Bulgaria's move from communism to capitalism.

As you would expect from an experienced cinematographer, Christov is never short of ideas and his own DoP Krum Rodriguez captures everything beautifully, from achingly good black and white scenes, which may or may not be a figment of Batko's imagination, to the period detailing. In this world where snow sometimes seems to fall upward and snorting snails is considered a perfectly reasonable hobby, everything has an absurdist edge. Todorov skewers political posturing of all colours, suggesting that Batko may be less of a chameleon than those who claim to be radical thinkers but who quickly change their views to match what is in the background if they think it will help them acquire power. It doesn't matter who is in charge, the truth can still be altered.

The number of satirical layers does occasionally threaten to smother the film but Vidinliev - a pop star in Bulgaria but surely destined for more screen roles after this - is a compelling central figure, scampering around this Kafka-esque set-up like a man with the keys to the castle. And if the final black and white scenes feel like a punchline too many, the earlier pay-off to Batko's machinations is satsifyingly water tight. The world may have lost a cinematographer but it has gained an inventive and exciting director.

Reviewed on: 25 Jun 2013